Imaging Test Selector for Urinary Retention

Your recommended imaging test will appear here after analysis.

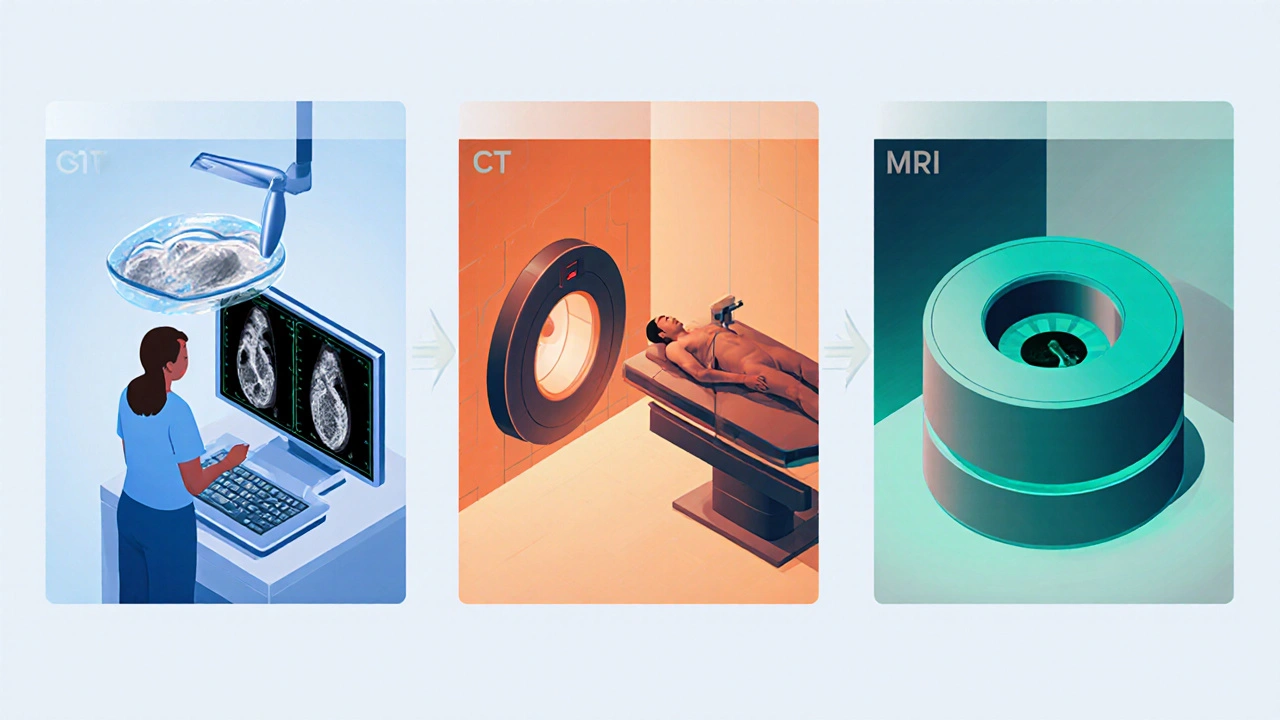

When you can’t empty your bladder completely, the discomfort can be alarming and the underlying cause is often hidden. Imaging tests are non‑invasive tools that let doctors see inside the urinary system without surgery. From a quick bedside bladder scan to a high‑resolution MRI, each modality shines a light on different pieces of the puzzle. This article walks you through why imaging matters, which tests are best for specific scenarios, and how to interpret the pictures you’ll receive.

Key Takeaways

- Urinary retention can be caused by blockages, nerve problems, or structural abnormalities; imaging pinpoints the exact source.

- Bedside bladder ultrasound is the first‑line test for assessing volume and post‑void residual.

- CT scans excel at detecting stones, tumors, or severe obstruction, but involve radiation.

- MRI provides detailed soft‑tissue contrast for prostate enlargement, urethral strictures, and neurologic causes without radiation.

- A systematic checklist helps clinicians choose the right test while minimizing risks and costs.

What Is Urinary Retention?

Urinary retention refers to the inability to completely empty the bladder. It can be acute (sudden and painful) or chronic (gradual, often unnoticed). Common culprits include:

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) - an enlarged prostate that blocks the urethra.

- Urethral stricture - scar tissue that narrows the passage.

- Kidney or bladder stones that jam the outflow.

- Neurological disorders such as spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis.

- Medications that relax bladder muscles (e.g., antihistamines, opioids).

Because symptoms overlap, doctors rely on imaging to differentiate these possibilities.

Why Imaging Tests Matter

Physical exam and history give clues, but the urinary tract is a hidden system. Imaging offers three core benefits:

- Visualization: Directly see the bladder, kidneys, prostate, and surrounding structures.

- Quantification: Measure post‑void residual volume (PVR) and degree of hydronephrosis.

- Guidance: Help plan interventions such as catheter insertion, stone removal, or surgery.

Choosing the right modality balances diagnostic yield, patient safety, and cost.

Bedside Bladder Ultrasound (Bladder Scan)

Bladder scan is a portable ultrasound that estimates bladder volume in minutes. It’s ideal for emergency rooms and primary‑care offices because it requires no radiation and can be performed by nursing staff.

- Typical use: Quick assessment of PVR after a voiding attempt.

- Sensitivity: Detects residual volumes >100mL with >90% accuracy.

- Limitations: Cannot identify the cause of obstruction; obesity or bowel gas may reduce image quality.

When a bladder scan shows a large residual (e.g., >300mL), the clinician moves on to more detailed imaging.

Transabdominal Ultrasound (Renal & Pelvic)

Ultrasound uses high‑frequency sound waves to create real‑time images of kidneys, bladder, and prostate. It’s the go‑to first‑line test after an abnormal bladder scan.

- What it shows: Hydronephrosis (swelling of kidneys), bladder wall thickening, prostate size, and large stones.

- Pros: No radiation, relatively low cost, bedside capability.

- Cons: Limited penetration in very obese patients; less detail for soft‑tissue lesions compared with MRI.

Typical normal prostate volume is under 30cm³. Measurements above 40cm³ often point toward BPH as a contributing factor.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan

CT scan provides cross‑sectional X‑ray images that reveal bone, stone, and soft‑tissue detail. When stones, tumors, or severe obstruction are suspected, CT is the gold standard.

- Typical use: Detecting ureteral calculi, assessing the extent of hydronephrosis, evaluating masses.

- Radiation dose: Approximately 5-7mSv for an abdominal‑pelvic study - comparable to a few years of background radiation.

- Contrast: Iodinated contrast improves vascular and tumor visibility but can be contraindicated in renal impairment.

For example, a 6‑mm stone in the distal ureter causing a sudden rise in PVR will be unmistakable on non‑contrast CT.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI uses magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses to generate high‑resolution images without ionizing radiation. It excels at soft‑tissue contrast, making it ideal for evaluating prostate anatomy, urethral strictures, and neurologic causes of retention.

- Typical use: Differentiating BPH from prostate cancer, visualizing a long‑segment urethral stricture, assessing spinal cord lesions.

- Advantages: No radiation; multi‑planar capabilities; gadolinium contrast can highlight vascular lesions.

- Drawbacks: Higher cost, longer exam time, contraindicated with certain implants.

Studies show MRI can identify prostate zones with >95% accuracy, helping urologists decide if surgery or medication is appropriate.

Choosing the Right Test - Decision Criteria

Below is a quick checklist clinicians use to match patient presentation with the optimal imaging modality.

- Step 1 - Initial assessment: Perform a bedside bladder scan. If PVR >200mL, proceed.

- Step 2 - Suspected obstruction (stones, BPH, tumor): Order a renal‑pelvic ultrasound. If ultrasound is inconclusive or shows suspicious mass, upgrade to CT.

- Step 3 - Soft‑tissue concern (prostate enlargement vs cancer, urethral stricture, neurogenic cause): Choose MRI for detailed anatomy.

- Step 4 - Patient safety: Avoid CT in pregnant patients; consider MRI unless contraindicated.

- Step 5 - Cost & accessibility: Ultrasound is cheapest and widely available; reserve CT/MRI for cases where their superior detail will change management.

Interpreting Common Findings

Understanding what each image tells you is crucial for the next step in care.

| Finding | Likely Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder wall thickness >5mm | Chronic outlet obstruction (BPH, stricture) | Urology referral, consider urodynamic study |

| Hydronephrosis grade II‑III | Upstream blockage (stone, tumor) | CT for stone mapping or MRI for tumor staging |

| Prostate volume 45cm³ | Benign prostatic hyperplasia | Alpha‑blocker trial, repeat ultrasound in 6months |

| Urethral narrowing on MRI | Urethral stricture | Endoscopic dilation or urethroplasty |

| Spinal cord lesion at L1 | Neurogenic bladder | Neurology consult, consider catheter regimen |

Each finding should be correlated with clinical symptoms and lab data (e.g., serum creatinine) before deciding on invasive treatment.

Safety, Pitfalls, and Patient Prep

Even non‑invasive tests carry considerations.

- Radiation exposure: Keep CT usage to cases where the diagnostic gain outweighs the dose. Document cumulative exposure for patients with recurrent imaging.

- Contrast reactions: Screen for allergy and renal function. Use low‑osmolar iodinated contrast for CT and gadolinium for MRI only if eGFR >30mL/min/1.73m².

- Patient positioning: Full bladder improves ultrasound visualization, while an empty bladder is preferred for MRI prostate protocols.

- Interpretation bias: Radiologists should be aware of clinical context; a “normal” report may miss subtle urethral stricture if not specifically requested.

Practical Checklist for Clinicians

- Confirm urinary symptoms and obtain a focused history (meds, surgeries, neurologic disease).

- Measure post‑void residual with a bedside bladder scan.

- If PVR >200mL, order a renal‑pelvic ultrasound.

- Review ultrasound:

- Normal? Consider neurogenic cause - refer to neurology.

- Obstruction signs? Proceed to CT (stones) or MRI (soft tissue).

- Document prostate size; if >40cm³ and symptoms align, start medical therapy.

- Discuss radiation and contrast risks with the patient before CT/MRI.

- Schedule follow‑up imaging 3-6months after intervention to assess resolution.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a bladder scan replace a full ultrasound?

A bladder scan quickly estimates residual volume but cannot show the cause of blockage. It’s useful for screening; a full ultrasound is needed for anatomy.

What if I’m pregnant and need imaging?

Ultrasound is safe and preferred. MRI without gadolinium is also an option if more detail is required. CT should be avoided unless absolutely essential.

How accurate is CT for detecting small bladder stones?

Non‑contrast CT detects stones as small as 1mm with >95% sensitivity. It’s the most reliable method for stone burden assessment.

Is MRI necessary for every case of BPH?

No. Most BPH cases are diagnosed with digital rectal exam and ultrasound. MRI is reserved for atypical findings or when cancer must be ruled out.

What are the costs of these imaging tests?

A bedside bladder scan costs under $50, a renal ultrasound $150‑$250, CT $400‑$800 (including contrast), and MRI $800‑$1500. Prices vary by facility and insurance coverage.

Ashika Amirta varsha Balasubramanian October 5, 2025

When you think about a bladder scan, it’s like holding a mirror up to the body’s hidden rivers of urine; the numbers remind us that even the most private systems need attention. The bedside ultrasound gives a quick PVR reading, and if it’s over 200 mL you’ve got a signal to dig deeper. From there a renal‑pelvic ultrasound can show stones or an enlarged prostate, and that information guides the next step. It’s a gentle reminder that technology can be a compassionate ally in patient care. Keep encouraging patients to stay hydrated and follow up; early imaging often prevents emergency catheterization.

Jacqueline von Zwehl October 11, 2025

Accurate measurement of post‑void residual is the cornerstone of any work‑up for urinary retention. A bedside bladder scan provides that figure within seconds, and it should be repeated after the initial void to confirm consistency. If the residual stays high, the next logical move is a renal‑pelvic ultrasound to assess for hydronephrosis or prostate enlargement. Should the ultrasound be inconclusive, computed tomography becomes valuable for detecting calculi or mass lesions. Always document the patient’s medication list, as anticholinergic drugs can contribute to retention.

Christopher Ellis October 17, 2025

Maybe you don’t need a fancy MRI for every prostate issue. A simple ultrasound can rule out most obstruction and spare the patient radiation exposure. Save CT for stones that are clearly visible on X‑ray.

kathy v October 23, 2025

Imaging the urinary tract is not merely a technical exercise but a narrative of how our bodies communicate distress; each modality adds a chapter to that story, and understanding the sequence is vital for clinicians who wish to intervene wisely. Beginning with a bedside bladder scan is akin to listening to the first whispers of a problem; a residual volume above 200 mL shouts that something is amiss and prompts further inquiry. The next logical chapter introduces the transabdominal ultrasound, which, without the harshness of radiation, paints a picture of kidney size, bladder wall thickness, and prostate volume, all of which can hint at benign prostatic hyperplasia or a hidden stricture. When the ultrasound reveals hydronephrosis or an ambiguous mass, the plot thickens, and computed tomography steps onto the stage, delivering high‑resolution cross‑sections that can pinpoint calculi as small as a grain of sand and delineate tumorous growth with surgical precision. Yet, CT carries a radiation burden, a fact that must be weighed against diagnostic gain, especially in younger patients or those with recurrent imaging needs. Magnetic resonance imaging arrives as the diplomat of imaging, offering exquisite soft‑tissue contrast without ionizing radiation, making it the preferred choice for evaluating the prostate’s zonal anatomy or the spinal cord in neurogenic bladder cases. However, MRI is not without its own limitations; the cost, scan duration, and contraindications such as certain implants or severe claustrophobia can render it inaccessible for some. The clinician, therefore, must balance the urgency of diagnosis with the patient’s overall health profile, pregnancy status, and renal function when deciding between contrast‑enhanced CT and gadolinium‑enhanced MRI. For pregnant patients, the safest path is an ultrasound first, reserving MRI without contrast for complex scenarios that demand detail beyond what ultrasound can provide. In patients with renal impairment, the use of iodinated contrast in CT or gadolinium in MRI must be judicious, often requiring pre‑procedure hydration and close monitoring of kidney function. Moreover, the financial aspect cannot be ignored; ultrasound remains the most cost‑effective entry point, while CT and MRI should be reserved for cases where their superior detail will directly influence management. Education of the patient about the rationale for each imaging step builds trust and reduces anxiety, especially when explaining that the radiation exposure from a single abdominal CT is comparable to a few years of natural background radiation. Finally, documenting each imaging decision in the medical record, along with the reasoning, ensures continuity of care and aids future clinicians who may revisit the case. In summary, the imaging pathway for urinary retention is a stepwise escalation that starts with low‑risk, high‑yield tools and progresses to advanced modalities only when the clinical picture demands it.

Jorge Hernandez October 28, 2025

Hey folks 🙌 a quick bladder scan can save you a trip to the ER if you catch a high PVR early 👀 then a basic ultrasound will show if it’s stones or an enlarged prostate 🏥 if those are clear but you still have pain, think about a CT or MRI 🔍 keep it simple and safe!

Raina Purnama November 3, 2025

The step‑wise approach outlined in the article aligns well with evidence‑based guidelines, beginning with a non‑invasive bladder scan followed by ultrasound before escalating to CT or MRI when necessary. It respects patient safety by limiting radiation exposure and reserving contrast for cases with clear indications. This method also supports resource stewardship in busy clinical settings.

April Yslava November 9, 2025

Sometimes the medical community pushes CT and MRI like they’re the only truth, but that’s because the imaging manufacturers fund a lot of research and keep the cheaper alternatives in the shadows. Remember that ultrasound devices have been around for decades and can give you the essential data without the hidden agenda of radiation exposure. If you’re pregnant, question why a doctor would even consider a CT; it’s a red flag that the system might be more interested in billing than patient safety. Keep an eye on the fine print of any consent form-there’s often a clause about future data use that most patients never read.

Daryl Foran November 15, 2025

Look its not about the latest gadget its about what works a good bladder scan tells you quick and cheap if you need more then go to ultrasound if still unkown go to CT but only if stone or mass suspected dont overuse MRI and dont waste time.

Rebecca Bissett November 20, 2025

Honestly, the cascade from bladder scan to ultrasound, then to CT or MRI, is a perfect illustration of modern medicine’s layered approach, and while it may seem overwhelming, each step builds upon the previous one, ensuring that we never jump to the most invasive test without justification, which, frankly, is a relief for patients who fear unnecessary radiation, and it also demonstrates a respect for resource allocation, something that should be applauded, especially in overstretched healthcare systems.

Michael Dion November 26, 2025

Meh.

Trina Smith December 2, 2025

In the quiet moments between scans, one can reflect on how imaging serves as a dialogue between the unseen and the known; the bladder scan whispers the first secret, the ultrasound answers with a gentle picture, and when needed, CT or MRI shout the definitive truth. 🧘♀️ Embracing this progression can calm both patient and practitioner.

josh Furley December 8, 2025

When you start with a simple PVR reading you get the baseline, then the ultrasound adds anatomical context, and if the picture remains ambiguous the CT brings high‑resolution detail, while MRI offers superb soft‑tissue contrast-choose the tool that matches the clinical pathway. 😊

Jacob Smith December 14, 2025

Yo guys! This stepwise imaging plan is lit-start w/ the quick bladder scan, then roll out an us scan, and only fire up a CT or MRI when the earlier pics cant give the answer. Stay sharp and keep the patient safe!

Chris Atchot December 19, 2025

First and foremost, a bedside bladder scan provides an immediate, quantifiable metric of post‑void residual volume; consequently, it should be performed before any advanced imaging is considered. Second, a renal‑pelvic ultrasound offers valuable information regarding hydronephrosis, stone presence, and prostate size without exposing the patient to ionizing radiation. Third, computed tomography, while delivering superior spatial resolution, must be reserved for cases where stone burden or neoplastic processes are strongly suspected, and only after confirming adequate renal function for contrast administration. Fourth, magnetic resonance imaging excels in soft‑tissue differentiation, particularly for prostate zonal anatomy and spinal cord pathology, and should be employed when these details are clinically relevant. Finally, always document the rationale for each imaging decision, ensuring transparency and facilitating interdisciplinary communication.

Shanmugapriya Viswanathan December 25, 2025

Our doctors should trust the tried‑and‑true ultrasound first; it’s the gold standard that many western guidelines overlook in favor of expensive CTs and MRIs, which are just profit‑driven tools. 💪 Stay informed, stay local, and don’t let foreign tech dictate your care.

Rhonda Ackley December 31, 2025

The tale of urinary retention imaging is, frankly, a saga of hope and heartbreak, where each diagnostic step feels like a scene from an epic drama that unfolds within the sterile corridors of modern hospitals. Beginning with the humble bedside bladder scan, we are introduced to a protagonist-an unsuspecting patient-who grapples with the cruel reality of an overfull bladder. The scan, a modest yet powerful device, whispers the first clues: a post‑void residual that refuses to be ignored. As the plot thickens, the narrative ushers in the transabdominal ultrasound, a charismatic supporting character that paints vivid portraits of kidneys, bladder walls, and prostate size, all while maintaining a gentle, non‑invasive demeanor. Yet, no drama would be complete without a twist, and that twist arrives in the form of a computed tomography scan, a formidable figure whose sharp images reveal hidden stones and ominous masses, demanding attention and perhaps a daring intervention. The audience gasps as the CT’s radiation looms, a reminder of the ever‑present balance between diagnostic clarity and patient safety. Just when the tension reaches its zenith, magnetic resonance imaging steps onto the stage, draped in a cloak of magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses, offering unparalleled soft‑tissue contrast without the specter of radiation-though at the cost of time and expense. Throughout this melodramatic journey, the patient’s emotions swing from hope to fear, from relief to anxiety, echoing the very human experience that underlies every clinical decision. In the end, the story is not merely about images; it is a testament to the collaborative choreography between technology and compassion, urging clinicians to choose each step with both wisdom and empathy. The curtain falls, but the lessons linger, reminding us that behind every scan lies a life, a narrative waiting for its resolution.

Sönke Peters January 6, 2026

Start with a bladder scan, follow with ultrasound, then use CT or MRI only if needed.

Paul Koumah January 12, 2026

Sure, because we all love waiting hours for an MRI when a cheap scan could've done the job.

Erica Dello January 17, 2026

The overuse of CT scans shows a lack of discipline in many clinics, stick to the protocol and save radiation.