When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic company to challenge that patent gets a special prize: 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version. Sounds fair, right? But here’s the twist - the brand-name company can still launch its own version of the same drug, just without the brand name. This is called an authorized generic, and it’s legal. And it’s one of the biggest reasons why the 180-day exclusivity rule doesn’t always work the way it was meant to.

What Is the 180-Day Exclusivity Rule?

The 180-day exclusivity rule comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. It was designed to speed up generic drug access without killing innovation. The idea was simple: if a generic company spends millions suing a brand-name drug maker over a patent, they deserve a head start in the market. That head start is 180 days - during which no other generic company can sell the same drug, even if their paperwork is ready.

But there’s a catch. The exclusivity doesn’t start the moment the FDA approves the generic. It starts when the company actually starts selling it. And it only kicks in if the generic company files a Paragraph IV certification - a legal notice saying they believe the brand’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. That’s not easy. It triggers a lawsuit from the brand, which can delay approval for up to 30 months. So the generic company is betting $2-5 million on a legal gamble.

What Are Authorized Generics?

An authorized generic isn’t a knockoff. It’s the exact same pill, made by the same company, in the same factory, with the same ingredients. The only difference? No brand name on the box. The brand-name company sells it directly to pharmacies as a generic. It’s legal because the FDA doesn’t require a separate approval for it. The brand just changes the label and ships it out.

This isn’t a loophole. It’s built into the system. And it’s common. Between 2005 and 2015, about 60% of the time a generic company got 180-day exclusivity, the brand launched an authorized generic at the same time. That means the first generic company isn’t alone on the shelf. It’s competing against its own former product - now cheaper, with no marketing.

Why This Hurts Generic Companies

Imagine you’re the first generic company. You spent $3.2 million on legal fees, hired a team of lawyers and regulatory experts, and finally got approval. You launch. You expect to capture 80% of the market. Instead, the brand drops its authorized generic on day one. Suddenly, you’re not the only game in town. You’re one of two. And the brand’s version is already trusted by doctors and pharmacists.

Studies show that when an authorized generic enters the market during the 180-day window, the first generic’s market share drops from 80% to about 50%. That’s a 30-50% revenue loss. In some cases, it’s hundreds of millions of dollars. Teva lost $287 million in 2019 when Eli Lilly launched an authorized generic of Humalog while Teva had exclusivity. That’s not an outlier. It’s the new normal.

Smaller generic companies are especially vulnerable. They don’t have the cash to fight back. Many now avoid Paragraph IV challenges altogether because the risk isn’t worth it. Drug Patent Watch found that 78% of first applicants now negotiate deals with brand companies to delay authorized generic launches - often in exchange for dropping their patent challenge. That’s not competition. That’s collusion dressed up as settlement.

Who Benefits?

At first glance, consumers win. Prices drop faster when two versions of the same drug compete. A 2021 RAND study found prices were 15-25% lower when an authorized generic was on the shelf alongside the first generic. That’s real savings for people paying out of pocket.

But here’s the problem: those savings come at the cost of the system’s original incentive. The Hatch-Waxman Act was supposed to reward companies that took on the legal risk. If those companies can’t profit from their wins, they won’t take the risk. And if no one challenges patents, brand-name drugs stay expensive longer. The FDA estimates that since 1984, Hatch-Waxman has cut drug approval delays by 3.2 years on average - saving $2.2 trillion in healthcare costs. But that’s only true if generic companies keep challenging patents. And they’re starting to back off.

What’s Being Done About It?

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has been pushing for changes since 2010. They’ve filed 15 antitrust lawsuits against brand companies accused of using authorized generics to block competition. In 2022, the FTC recommended Congress amend the Hatch-Waxman Act to ban authorized generics during the 180-day window. They estimate this would boost first-generic revenues by 35% - and bring back the incentive to sue.

Legislation like the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act has been introduced multiple times since 2009. It would make it illegal for brand companies to launch authorized generics during the exclusivity period. So far, it’s never passed. Brand-name drug groups like PhRMA argue that banning authorized generics would hurt consumers by slowing price drops. But critics say the system is already broken - and the only thing it’s protecting is the brand’s profit margin.

In 2023, FDA Commissioner Robert Califf told Congress he supports clarifying the law to stop authorized generics during exclusivity. That’s a big deal. The FDA has mostly stayed out of the political fight. Now they’re taking a side.

What Should Generic Companies Do?

If you’re a generic manufacturer, you can’t afford to ignore this. Here’s what works:

- Plan 12-18 months ahead. Preparing a Paragraph IV ANDA takes time - and money.

- Build a team: legal, regulatory, and commercial staff must work together. One misstep can cost you the exclusivity.

- Track the trigger date. Exclusivity starts when you ship the product, not when you get approval. Don’t ship early. Don’t delay.

- Negotiate. If you’re going to challenge a patent, try to get a deal that delays the authorized generic. Most big companies now do this.

- Know the risks. If the brand has a history of launching authorized generics, your chance of profit drops sharply.

And if you’re a small company? Be careful. The cost of failure is high. Many now wait for other companies to challenge patents first - then enter the market after exclusivity ends. It’s safer. But it’s slower. And it doesn’t help the system work as intended.

The Bigger Picture

The 180-day exclusivity rule was meant to be a spark. It was supposed to ignite competition, lower prices, and get life-saving drugs to patients faster. But now, it’s more like a flickering candle. The brand companies found a way to dim it without breaking the law.

The U.S. generic market is worth $65 billion. It fills 90% of prescriptions. But the incentive to challenge patents is fading. And if that trend continues, we’ll see fewer generics, slower price drops, and higher drug costs over time.

This isn’t just a legal issue. It’s a public health issue. The system was built to protect patients. Now, it’s being used to protect profits. And unless Congress steps in, the next generation of patients might pay more - not less - for the drugs they need.

Can a brand-name company launch an authorized generic before the 180-day exclusivity period starts?

No. The brand can’t launch an authorized generic until the first generic company has received FDA approval and begun commercial marketing. But once that happens, the brand can launch immediately - even on the same day. The exclusivity period only blocks other generic companies, not the original brand.

Does the FDA approve authorized generics separately?

No. Authorized generics don’t need a separate FDA approval. They’re manufactured under the same New Drug Application (NDA) as the brand-name version. The company just changes the label and sells it as a generic. This is why they’re legal and fast to launch.

What happens if two companies file for 180-day exclusivity on the same day?

If two or more companies file substantially complete ANDAs with Paragraph IV certifications on the same day, they can share the 180-day exclusivity period. This was clarified by the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. Both companies get the same market advantage - but neither gets a full 180 days alone.

Can a generic company lose its 180-day exclusivity?

Yes. The FDA can revoke exclusivity if the company doesn’t begin commercial marketing within 75 days of approval, or if they stop selling the drug for more than 180 days. Many small companies lose part of their exclusivity due to delays in shipping or miscommunication with distributors.

Why hasn’t Congress fixed this yet?

Because the pharmaceutical industry spends billions lobbying against changes. Brand-name companies argue authorized generics lower prices and benefit consumers. Generic companies say the system is rigged. Without strong public pressure, lawmakers are hesitant to upset either side. The issue remains stuck in political gridlock.

Are authorized generics the same as counterfeit drugs?

No. Authorized generics are legal, FDA-approved versions of the brand-name drug. Counterfeit drugs are fake, often made overseas, and sold illegally. Authorized generics are made in the same factory as the brand, with the same quality control. The only difference is the label.

Myson Jones December 3, 2025

So the system was meant to help patients, but now it’s just a game of who can outmaneuver whom legally? Kinda sad when the goal shifts from access to profit. I get why companies do it - business is business - but when you’re talking about life-saving meds, it feels like the rules got twisted.

parth pandya December 4, 2025

authorized generic is such a sneaky move by big pharma… they just change the label and boom, no more exclusivity effect. i mean, how is that fair? the generic company took all the risk, and the brand just rides on it. sad but true. #pharmarot

Albert Essel December 5, 2025

The Hatch-Waxman Act was a brilliant compromise - incentivizing innovation while accelerating access. But the emergence of authorized generics represents a structural erosion of that compromise, not a violation of it. The law never prohibited it, and courts have consistently upheld the practice. The real issue isn’t legality - it’s whether the policy outcome still serves the public interest. If generic manufacturers are retreating from Paragraph IV challenges, then the system’s core incentive is failing, and that’s a public health concern, not just a corporate one.

Charles Moore December 6, 2025

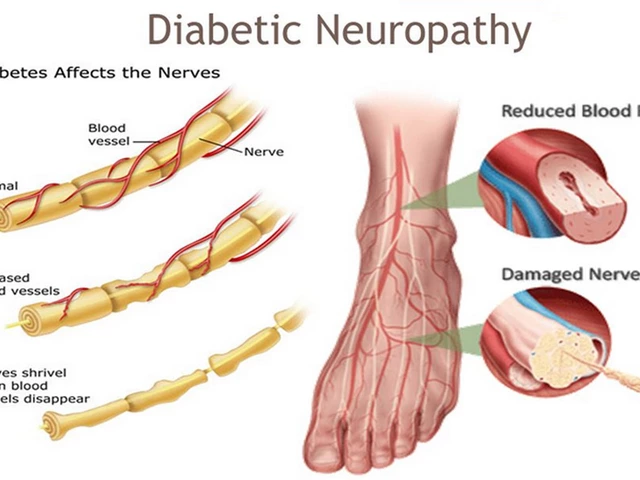

It’s wild how something designed to help people end up helping corporations more. I’ve seen this play out with my uncle’s insulin - he pays less when generics are around, but when the brand drops their own ‘generic’ version, prices don’t drop as much as you’d think. The system feels rigged, but nobody’s got the guts to fix it. Maybe we need more patients speaking up, not just lawyers and lobbyists.

James Kerr December 7, 2025

So the brand just slaps a new label on the same pill and calls it a day? 😅 That’s like if McDonald’s launched a ‘generic’ Big Mac right after a rival opened up. Kinda dirty, but legal. Guess we’re all just paying for the drama.

shalini vaishnav December 9, 2025

Why are Americans so naive? In India we know that pharma patents are just tools for Western corporations to bleed developing nations. This 180-day nonsense? A distraction. The real problem is that the U.S. allows drug monopolies for 20 years - that’s the crime. Stop focusing on authorized generics and fix the root: patent abuse. You think this is bad? Wait till you see what happens with biosimilars.

bobby chandra December 9, 2025

Let me break this down like I’m explaining it to my cousin at a BBQ: The brand’s playing chess while the generics are playing checkers. The brand gets to drop a second version - same pill, same factory - and suddenly the underdog’s got a ghost haunting their payday. That’s not competition. That’s sabotage with a FDA stamp. And now? The little guys are walking away. That’s not progress. That’s surrender.

Archie singh December 9, 2025

Pathetic. The system is broken because the generics are weak. If you can’t handle a little competition from your former partner, you shouldn’t be in pharma. This isn’t a scandal - it’s capitalism. Stop crying about lost profits and learn to adapt. The FDA didn’t create this mess - you did.

Katherine Gianelli December 10, 2025

I just want to say - thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I see this every day. Patients ask why their insulin is still $400 even though there’s a ‘generic’ out there. I have to explain that it’s the same drug, just cheaper because the brand made it themselves. It breaks my heart. We need to fix this - not just for profits, but for the people who can’t choose between meds and groceries. This isn’t politics. It’s human.